Where Video Lives Now: A Practical Map of Film Audiences

Updated February 2026

Last Friday night, you watched two films back to back. The first was in a cinema, a room full of strangers sharing the same hush, no glowing phones, no pauses, just a slow build that felt electric. Later, you played a short from the same director on your phone, one earbud in, half relaxed, half reachable. Notifications popped up. You paused to reply. You rewound a moment you missed. Halfway through, it started to feel like homework, not because the film suddenly got worse, but because the contract changed. Same story, different room, different rules.

That contract is the real starting point for audience thinking. Viewers do not feel demographics first, they feel whether the work is keeping its promise, which aligns with research on how expectations shape interaction and satisfaction in audience expectations and viewer interaction research.

If you are scripting, editing, commissioning, or programming film and video, the quickest way to get better outcomes is to predict what kind of attention you can realistically earn in a given moment. This post gives you a practical map for that, with tools you can screenshot, tables you can reuse, and a set of decisions that travel across cinema, TV, and mobile without turning into platform arguments.

Fast route if time is tight

If you want the map in one glance, start here and then jump to the sections you need. These seven dials cover the decisions most people get stuck on.

Start with the contract not the platform

The useful starting point is the deal you are asking the viewer to accept. What do they have to give, time, focus, emotional effort, patience? What do they get back, escape, insight, catharsis, a laugh, a feeling of belonging? This deal changes with posture, company, and interruption level, and it changes again when the cost of leaving drops to zero. When the deal is clear, people forgive rough edges because they know what they are here for. When it is fuzzy, even beautiful work can feel like effort because the viewer keeps asking what the point is.

A good habit is to treat cinema, TV, and phone as three rooms with different rules. Cinema is high commitment attention with stronger social norms. Home viewing is lower friction attention where pausing is normal. Phone viewing is often high interruption attention where leaving costs almost nothing. If you want a clean mental model for how these rooms create different behaviours, the clearest internal reference point is how people switch between cinema and streaming.

Cinema programming thinking helps here because it begins with motivations and habits rather than abstract categories. It treats audiences as people with patterns, and it pushes you to describe what they want and how you communicate it, which is captured well in cinema audience motivations and habits.

Shared watching also has a real mechanism behind it. Research suggests that shared emotional experiences can increase social connection, which helps explain why a room full of strangers can feel linked by the credits, in shared emotion builds social bonds. Studies on shared experience also suggest that synchronised reactions can strengthen bonding, which is one reason the cinema hush can feel different even when you would never speak to the person next to you.

Viewing Contract Canvas

This is designed to be screenshot friendly and used repeatedly. Answer these before you write, shoot, or cut anything, and be honest with yourself about the cost.

The promise

What is the viewer meant to get, in plain language, and why should they care?The cost

What are you asking the viewer to give, time, focus, emotional effort, patience?The payoff timing

When do they get their first real reward, and how often do you pay them back?The interruption plan

If they miss 15 seconds or pause twice, can they still follow the thread?The leaving cost

How easy is it to abandon, and what makes staying feel worth it?

Viewer Mode Matrix

This matrix makes the contract concrete. The same person becomes a different viewer depending on posture and company, so it is more useful to pick a mode than to argue platforms. Use this to choose pacing, structure, and emphasis that fit the way the story will actually be watched.

| Viewer mode | Typical context | What the viewer wants | Main risk | Best craft move |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lean back | TV and sofa | Comfort and low effort immersion | Drift and multitasking | Clear beats and gentle re entry cues |

| Lean forward | Laptop and intentional watch | Detail and meaning | Slow starts without direction | Early proof and visible progression |

| On the go | Phone and scrolling | Fast orientation and quick payoff | Instant abandonment and sound off viewing | Premise fast plus short payoffs |

| Communal | Cinema or shared home watch | Ritual and shared feeling | Dead air that breaks the room | Tension you can feel and reaction moments |

Quick definitions that make the map easier

If you are new to these ideas, this quick glossary helps the rest of the post land. The definitions are deliberately plain so you can use them while planning or editing.

| Term | Plain meaning | Why it matters in practice |

|---|---|---|

| Viewing contract | The deal the viewer thinks they are making | If the deal is clear, viewers forgive rough edges |

| Viewer mode | How someone is watching right now | Mode predicts pacing needs better than platform labels |

| Re entry | How easy it is to return after interruption | Good re entry protects attention in real life viewing |

| Payoff | A reward that proves the promise is real | Regular payoffs stop the story feeling like effort |

If you want an academic but accessible overview of film audience study across venues and methods, audience research reading list is a clean starting point that points to the field without becoming heavy.

The attention bargain in a world of divided focus

Attention did not disappear, it became negotiated. A lot of viewing happens alongside choice, interruption, and parallel inputs, which means your work is constantly answering a silent question. Is this worth staying with right now? If your story cannot carry that question, it starts to feel like effort and viewers look for something that costs less to follow. If it can carry the question, the viewer protects it, even when the room is noisy and the day is busy. The irony is that the tools that free us from commitment can also make shared surrender rarer, because the exit is always within reach.

This is also where it helps to name the bargain directly, because it turns vague advice into a repeatable decision. The internal reference for that idea is the attention bargain in practice, which frames attention as a trade you pay back with clarity, rhythm, and proof rather than constant urgency.

A few signals that keep this grounded

In the US, streaming captured 47.5 percent of total TV viewing in December 2025, which is a useful reminder that switching and choice are not edge behaviours, they are the default environment for a lot of viewing, reported in streaming share of TV viewing.

Across US consumers, media and entertainment companies compete for an average of six hours per day of attention, and that number is not expanding, which is a simple way to understand why storytelling has to earn its place, captured in six hours of media time.

Cinema still sits in that mix as a distinct attention contract. A US exhibition summary notes that moviegoing remains widespread, citing research that 77 percent of Americans visited a theatre in the past 12 months, which is useful context when you want to talk about communal attention as a live behaviour, in moviegoing remains a mass habit.

If you want one UK anchor for global balance, the latest official figures are in UK cinema and production figures, which includes box office and admissions alongside production spend.

These signals do not tell you what to make. They tell you what kind of room you are making it for, and why clarity and re entry are no longer optional.

| Signal | What it suggests | What to do with it |

|---|---|---|

| Streaming can dominate share | Choice and switching are built into viewing | Make the promise legible and keep payoffs arriving |

| Six hours is the attention ceiling | Your story competes inside a fixed budget | Reduce cognitive load and make the next step obvious |

| Cinema remains a mass behaviour | Communal attention still exists at scale | Build for tension and shared reaction moments |

Second screens raise the price of confusion because a missed beat can turn into a lost thread. Experiments have found that second screen viewing can increase cognitive load and reduce recall and comprehension, which is a useful directional reminder when you are deciding how much subtlety your structure can safely carry, in second screen cognitive load effects.

If you want to keep that idea practical rather than academic, the internal companion is why second screens change watching, which treats re entry as a design problem rather than a complaint about phones.

Payoff Ladder

This ladder keeps pacing honest and stops you relying on vague momentum. It also gives you a clean way to fix edits that feel flat, because it forces you to name what the viewer gets and when.

| Payoff level | When it should arrive | What it looks like | How it earns attention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Micro payoff | Early | Clear promise and a reason to care | Reduces uncertainty and builds trust |

| Mid payoff | Middle | Proof twist or emotional lift | Rewards patience and renews momentum |

| End payoff | Final stretch | Resolution or reframing that feels earned | Turns time spent into meaning |

Re entry Toolkit

Most people do not abandon a story because they hate it. They leave because they lost the thread and the cost of re entering feels higher than the reward. Re entry cues fix that without turning your work into constant recap, and they are especially useful when you are designing for viewers who pause, scroll, or look away and then come back.

Repeat the goal in new words

Use visual anchors like a repeated object or location

Add mini summaries disguised as dialogue

Signpost turns like here is the problem and here is what changed

Plant micro questions that pull the viewer back into curiosity

If you want one internal lens on how generational habits shape attention expectations without turning it into stereotypes, how Gen Y and Z watch frames it as behaviour and context rather than labels.

Formats are behaviour choices not packaging

Format is not just a look, it is a viewing posture. Vertical suits quick orientation and short payoffs. Widescreen suits settling in and building tension. A long take can feel hypnotic in a cinema and exhausting on a phone, not because it is wrong, but because it is mismatched to the viewing contract. When the format and the mode match, viewers stop noticing the container and start noticing the meaning, and that is the simplest definition of good format choice.

A useful reality check is that performance data is often incomplete or hard to interpret, which makes it easy to copy surface trends rather than understand why something worked. That dynamic is explored clearly in video demand and viewing data.

If you want a clean internal map of how aspect ratios, edits, and distribution habits evolved together, how video formats shaped viewing habits frames it as behaviour change rather than a timeline of specs.

Production reality matters too. The phone is not only a screen, it is also a camera and a publishing tool, and Mobile Journalism also called MoJo makes that advantage practical when speed and authenticity matter.

Planning for the second room

Most viewing now happens in two stages. The first room is where the story begins (cinema, sofa, commute, feed). The second room is where it gets resumed, shared, clipped, debated, or ignored. Planning for both is less about “optimising” and more about protecting the experience when attention breaks.

Use this as a quick pre-flight before you lock the cut:

Name the first room. Where do you realistically expect the first watch to happen, and what do viewers have (time, sound, screen size, patience)?

Predict the second room. If it travels, where does it travel to — a group chat, a living room rewatch, a short clip, a reaction, a classroom?

Decide what must survive. If someone misses 15 seconds, watches sound-off, or drops in halfway, what single idea still lands?

Build a clean re-entry point. Add a moment that re-orients without repeating — a visual reset, a line that re-states stakes, a clear turn.

Choose the shareable unit. If one fragment represents the whole, what is it — and does it reflect the intent rather than distort it?

The goal is not to make everything “platform native”. It is to make the work resilient: clear when watched imperfectly, and still rewarding when watched properly.

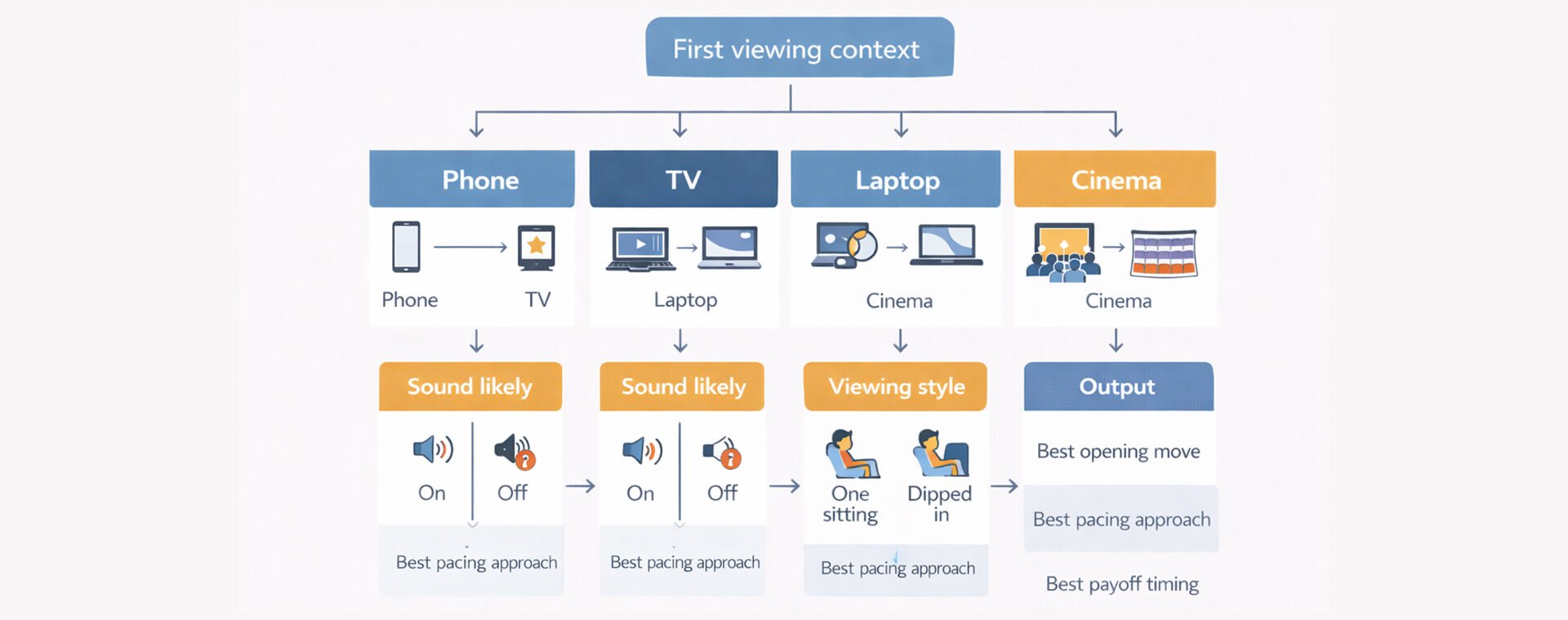

A format decision checklist

Before you lock anything in, answer these without hedging, because vague answers usually turn into vague edits.

What is the first viewing context, phone, TV, laptop, cinema?

What is the likely second context after sharing?

Is this watched in one sitting or dipped into?

Is sound likely to be on or off?

What single thing must still be understood if 15 seconds are missed?

Overused defaults and better alternatives

These defaults are common because they work in short bursts, but they often get overused and flatten meaning. Use this table as a quick quality filter when an edit feels busy but not memorable.

| Trend format | What it did well | Why it got overused | What to do instead |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant urgent pacing | Keeps attention in short bursts | No contrast so nothing lands | Speed up for steps slow down for meaning |

| Generic montage openers | Quick polish and momentum | Delays meaning and feels interchangeable | Open on a specific moment of friction or result |

| Glitch transitions | Signals disruption or a shift | Used as decoration not meaning | Cut on action or sound change |

| Kinetic typography overload | Improves clarity in noisy contexts | Text becomes the story instead of support | One key line at a time then clear it |

| Overgraded teal and orange | Instant cinematic shorthand | Same look across unrelated stories | Grade to the scene and the intended feeling |

| Overused whoosh and riser SFX | Adds perceived movement and impact | Replaces real story emphasis | Use room tone restraint and one chosen emphasis |

| Speed ramps | Makes movement readable and punchy | Becomes default energy filler | Hold a beat before impact then cut clean |

Interactivity and AI are changing what watching means

Watching used to be mostly one way. Now audiences often expect some form of participation, even if it is light. Participation can be social, structural, or commercial, and the key question is whether it strengthens meaning or competes with it. If participation clarifies the promise, it can raise attention because the viewer feels included rather than sold to. If participation becomes the main event, the story becomes decoration and the contract gets muddy. This is why the best interactive ideas feel invisible. They make the work easier to stay with, not harder.

A clear modern example is commerce inside the viewing flow, where watching and deciding happen in the same moment, explored in shopping inside the video frame.

If you want an accessible framing of communal watching as a social experience, films as social glue is a useful human layer that pairs well with the research on shared emotion.

Trust rules that keep your work credible

If you want this to stay useful and trustworthy, treat trust as part of craft, not an afterthought. The simplest check is whether the interactive layer clarifies what the viewer is meant to feel and understand, or whether it distracts from it. It also helps to separate speed from meaning, because a faster workflow is not the same thing as a stronger viewing contract, and AI doesn’t sign the contract. Clarity and trust do.

If participation clarifies meaning, it strengthens the contract

If participation competes with meaning, it weakens the contract

If AI is used, be clear where clarity matters, especially if something could mislead

Keep a human editorial layer for premise, ethics, and final judgement

Key takeaways you can plan with

If you want a practical way to plan film and video that people actually finish, start here. The viewer signs a contract even if they never name it. Attention is a trade you pay back with clarity and rhythm. Format is behaviour, not packaging, so choose posture first. Agency is powerful when it serves meaning, not when it shows off. Re entry is craft, so design for interruptions rather than pretending they will not happen.

A short playbook you can reuse

Write the contract in one sentence

Choose the viewing mode from the matrix

Pick the format that matches that mode

Place your micro payoff, mid payoff, end payoff

Add two re entry cues

Remove one moment that does not serve the promise

FAQs people actually ask

Do you need to choose between cinema and streaming?

No. Choose based on the contract you are offering. Cinema is high commitment attention when the event is worth it, and streaming is lower friction attention that has to survive interruption.

Is shorter always better now?

No. Clearer is better. Long form content can win when the contract is clear and payoffs keep arriving. Long form can be a feature film, a documentary, or a full length podcast episode, while short form is closer to a highlight reel, a trailer cut, or a TikTok sized story.

How do you stop a film feeling like homework on a phone?

Make the promise legible fast, keep micro payoffs frequent, and design re entry points so missing a short moment does not break the thread.

Where to go next

Intrigued by any of these? Click the articles below for a deeper dive.

| Article | Best for | Who it suits |

|---|---|---|

|

|

Deciding how pacing, payoff timing, and positioning change when the “room” changes, cinema, sofa, or phone | Writers, producers, programmers, and film students making choices about structure, release thinking, and audience expectations |

| Understanding why formats keep mutating, and what craft choices travel well across platforms without becoming trend chasing | Creators and commissioners choosing duration, framing, serial structure, and where a piece should live | |

| Designing lean-in interactivity that survives real-world friction, short attention, movement, light, noise, and drop-off | Brand teams, agencies, and small crews planning interactive formats that have to work outside ideal viewing conditions | |

| Making phone-shot work feel deliberate, clear, and watchable when the audience is already in scroll mode | Solo shooters, students, comms teams, and anyone producing fast-turnaround video for mobile viewing | |

| Planning interactive video where attention has a “job” to do, without breaking clarity or trust | E-commerce teams, performance marketers, product brands, and producers building video that needs to drive action |