Your Voice, Your Trust: AI Video Disclosure and Consent Checks

A model used to mean a person posing in a studio. Now it can also mean a system trained on huge volumes of footage, sometimes gathered through web scraping and web crawling, then used to generate or reshape video from a small set of inputs. And whose footage is that? It can be a YouTuber’s back catalogue, a content creator’s reels, stock libraries, or clips that look like they came from a big studio workflow. If you’re a brand assuming your campaign videos aren’t fair game, it’s worth thinking again. The same goes for anyone thinking it only targets Hollywood characters and scenes. If you’ve ever thought “our stuff is too niche to be worth copying”, that’s usually when it starts happening. Once something is online, it can be copied, analysed, and learned from, and the output doesn’t always look like an obvious copy.

AI can be genuinely helpful too. Used well, it can reduce the boring parts of production, improve accessibility through captions and translations, and help small teams move faster without lowering craft standards. The shift is useful, but it changes what audiences assume they’re watching, and what creators and brands can realistically protect. AI can remove friction, but it can also blur consent, credit, and what counts as a real moment.

In practice, the line between impressive and unacceptable can be crossed fast when real people and recognisable likenesses are involved. Once audiences feel reality has been borrowed, trust drops and it can be difficult to win back. SAG-AFTRA calling it blatant infringement is a useful reminder that consent and rights aren’t edge concerns. They’re part of the viewing contract when a clip plays like proof. It’s a loud reminder that consent, credit, and clear labelling aren’t theoretical once tools can generate clips that look cinematic and convincing.

When a clip plays like proof, the difference between “impressive” and “misleading” often comes down to whether it feels earned. That trust judgement is shaped by what viewers think was captured versus constructed, which is why trust in human vs synthetic video matters before you get into the practical checks.

Quick navigation

If you're short on time, jump straight to the section you need. These cover the essentials for AI video disclosure, consent, style protection, and brand safeguards.

Disclosure and consent quick check

AI is at its best when it reduces grunt work and leaves judgement to you. It can be at its worst when it simulates reality without giving viewers enough context to understand what they’re seeing.

A useful rule is simple. The more the video asks the audience to believe something happened, the more careful you need to be about consent, disclosure, and proof. If a reasonable viewer could feel misled once they knew how it was made, it probably needs a clearer label.

It’s also fine to skip AI entirely. Some crews prefer a fully manual workflow because it keeps decision-making transparent and reduces edge-case risk. If the job can be done cleanly without synthetic steps, that choice can be part of your trust strategy.

Use this check as a quick habit before you publish.

What is the video asking the viewer to believe happened?

If it implies a real interview, endorsement, or event, can you show that it happened?

If anything is synthetic or heavily edited, where will the disclosure appear in the viewing experience?

Do you have explicit consent that covers this use of a person’s likeness or voice?

If someone challenged it publicly, could you explain your process calmly and clearly?

In the UK, transparency expectations get sharper when personal data is involved, and it’s worth reading what the regulator actually says rather than guessing. Information Commissioner’s Office guidance on transparency in AI is a solid reference point.

A testimonial that wasn’t filmed

This is where things go wrong in the real world.

A tech company launches a new productivity app. They need a strong customer testimonial, and trust is part of the job.

They bring in Sarah, a real mid-level manager, for a voice recording session. She speaks her lines naturally, genuine enthusiasm, natural pauses, real emotion.

The agency then takes a handful of high-quality stills of Sarah and a clean voice recording, feeds them into a generative system along with scripted answers, and prompts it to produce a lifelike 60-second testimonial. The result can fabricate motion, facial performance, and even a polished studio environment that never existed.

The eyes blink naturally. The mouth moves in sync. The light catches her glasses when she leans forward.

It looks like Sarah sat down in a professional studio and answered questions live on camera.

But she didn’t.

The more a video functions as proof, the more consent, disclosure, and documentation matter.

Months later, someone clocks it. A side-by-side appears online. The comments turn into questions. The story stops being the product and becomes whether the brand tried to pass something off as real. That’s how reputational damage starts, and it’s rarely quick to undo.

The more a video functions as proof, the more consent, disclosure, and documentation matter. A version that holds up can still use AI, but it stays honest about what was captured and what was constructed. Because if the truth comes out later and it often does, the brand is the one left holding it. People feel misled, trust drops, and suddenly you’re spending time explaining the work instead of letting it do its job. Getting that confidence back can take a while.

If you want a commissioning guardrail for anything testimonial-shaped, use this.

If it is proof, capture something real

If it is synthetic, label it where people will actually see it

If it uses a real person, get consent that includes synthetic use

If it is scripted, say it is scripted

Place disclosure where it can’t be missed, with on-screen text near the start and the same wording again in the caption or description.

Platforms don’t always judge intent, they judge what it looks like to a viewer, so the safest approach is to label early and keep your paperwork tidy.

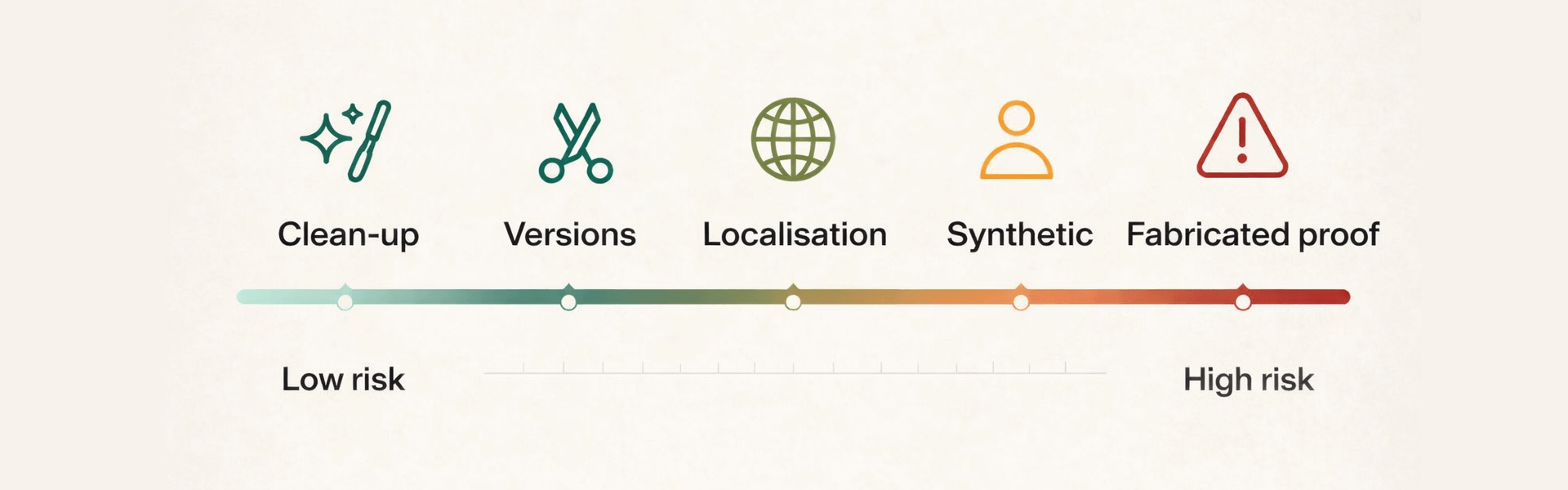

Match the tool to what the audience thinks they’re watching. This table shows safer AI uses by content type.

| Content type | What viewers assume | Safer way to use AI | Platform expectations and labels | Keep it trust-safe by avoiding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case study | The outcomes and quotes reflect something that happened. | Use AI to tighten structure, generate cut-downs, and localise. Keep source notes and approvals linked to the edit. | Claims and quotes tend to attract scrutiny. Keep a clean source trail, approvals, and a clear disclosure approach for any synthetic reconstruction. | Made-up quotes, synthetic before-and-after scenes, or data presented without a source trail. |

| Demo | The product behaves like this in the real world. | Use AI for cut-downs and translations. If anything is simulated, label it and keep proof of what was real. | Risk rises if results look captured but are simulated. Label simulations and be prepared to show what was actually recorded if questions come up. | Simulated results that look like captured performance without context. |

| Explainer | The brand is presenting information, not evidence of a real event. | Use AI for structure, b-roll ideas, captions, and accessibility. Disclose if visuals are generated. | Lower risk when it’s clearly informational, but viewers still benefit from simple labels for generated visuals so they are not guessing what is real. | Generated scenes that look like real footage of real people without a clear label. |

| Testimonial | A real person said this, and it reflects a real experience. | Film a real interview, then use AI for captions, clean-up, and language versions. Disclose any meaningful alteration on-screen. | If it plays like proof, expect higher scrutiny. Label synthetic or heavily altered elements early on-screen and keep consent documentation ready. | Synthetic performance presented as live proof, or stitched answers that change meaning. |

Protecting style as a creator or a brand

There’s a risk that doesn’t always look like theft at first glance. It can feel like recognition in the wrong place.

You spot a clip in a feed that holds for the half-beat you always hold. The push-in lands exactly when you’d land it. The music drops out with the same restraint you trained into your edits. It isn’t your file lifted and reposted. It’s your judgement, extracted and replayed, with no credit and no payment.

Then you notice the shots used are nearly identical to your carefully shot ones, even down to the location. Only small, subtle changes exist. You play them side by side, realising it’s too much of a coincidence.

This isn’t a Hollywood problem. Somehow your carefully planned shots are free to use with no credit. It lands as a weird mix of unease, frustration, and anxiety. And once you’ve seen it, you start watching feeds differently. Social media was already ablaze with short samples and knock-offs, but most people didn’t clock how wide this could spread. It starts to feel like anything online is treated as fair game, even when it clearly came from someone’s time, taste, and labour.

Brands can feel the same shock. You pay for a campaign that works because it feels distinctive, then a competitor in another market runs something uncannily similar. It might not be a frame-for-frame copy. It’s the same structure, the same rhythm, the same visual logic, close enough that your team starts asking how it happened.

Even at the Oscars level, the same dynamic applies. Imagine a film wins, and then months later a breakdown thread shows how parts of the look and sequence logic were effectively borrowed from another creator’s work, close enough to line up side by side. The conversation stops being about the win and becomes about what’s original and who gets credit. It doesn’t need a dramatic ending to hurt. The noise alone can swallow the moment, and it can follow the team into the next job.

The fastest way to reduce this risk is boring but effective. Make it easy to prove authorship and hard to quietly reuse your work.

Publish with consistent credit lines and dated exports, even for small jobs

Keep source files and short project notes so you can show what you made and when

Add a no-training clause and ask for a simple tool log on delivery

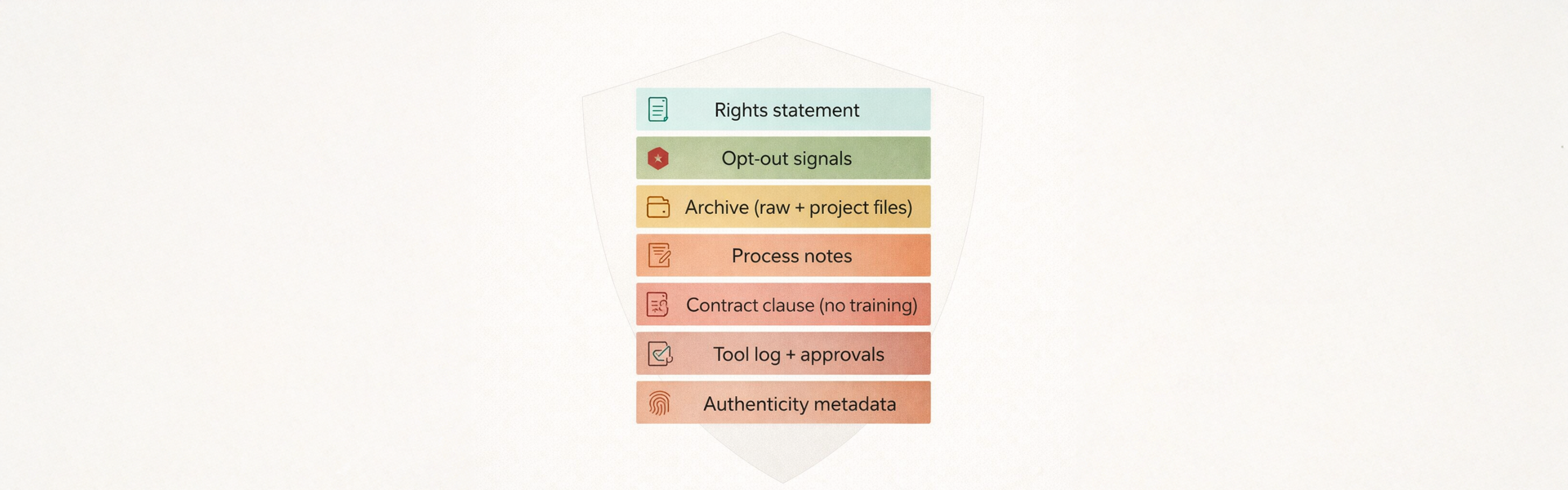

What to keep on file

A layered protection stack: combine rights, records, contracts, and metadata so trust and authorship are easier to prove.

If you’re asked how something was made, the answer tends to fall apart when nobody saved the boring bits. A simple keep-on-file habit prevents that.

The original raw footage or source files

Any consent and release forms, including synthetic use if relevant

The exact disclosure wording used, plus where it appeared

A short note listing tools used and what they were used for

Approvals, even if it’s just an email thread

If the conversation shifts to authorship, it helps to ground your claims in a primary source rather than opinion. The United States Copyright Office sets out how human contribution still matters in Copyright and Artificial Intelligence Part 2 on copyrightability.

If you want a concrete way to show provenance over time, content credentials are the standardised direction of travel. The clearest starting point is the C2PA Content Credentials standard.

Questions brands should ask

Brands are more likely to get burned not by AI itself, but by unclear sourcing, unclear consent, and a final piece that implies a real moment without earning that belief.

If you’re briefing an agency, these questions keep everyone honest without killing the creative.

What source material was used, and is it licensed or consented?

Where will disclosure appear, and will viewers actually see it?

Do we have explicit consent for likeness and voice use, including any synthetic performance?

What are we keeping on file if someone asks how it was made?

Can we produce a real alternative for anything that functions as proof?

A quiet risk sits underneath prompt-made content. Who owns the IP if a video is generated from a prompt? The answer can depend on where you are, how much human creative control is really in the final cut, and what the tool terms allow. In some cases, purely generated output can be harder to protect or enforce, which matters if you are expecting exclusivity. The safe move is to confirm rights in writing, not assume them.

If you want three questions that catch this early, add these to the brief.

Are we expecting this to be exclusive, and if so what rights can the supplier actually grant if parts are generated?

What human creative work is being contributed, and what parts are generated or automated?

What do the tool terms allow, and do we have written confirmation of output rights, plus any limits on reuse or training?

If you want something you can paste into a brief, this table captures the workflow.

| Area | What to ask or do | What to keep on file | Where it should show up |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sourcing | Confirm where footage, stills, and audio came from, and whether licences and releases cover this use. | Source list, licences, and release forms. | In the brief and delivery notes. |

| Consent | Get explicit permission for likeness and voice use, including any synthetic performance. | Signed release and scope of use. | In approvals and archive. |

| Disclosure | Agree wording and placement before edit lock so it isn’t an afterthought. | Final disclosure copy and where it appears. | On-screen early, and again in caption or description. |

| Tools | Ask for a simple tool log describing what was AI-assisted, and what was generated. | Tool list and a short process note. | In delivery notes and archive. |

| Evidence | If the video implies a real event or endorsement, confirm what evidence exists and whether any claims can be backed up. | Raw capture, transcripts, and approvals. | In the archive, and in claims review. |

If you want something you can publish without sounding corporate, here’s a transparency statement template.

We use AI tools in parts of our video workflow where they save time or improve accessibility

We do not use AI to fake real experiences, endorsements, or events

If something is generated or heavily altered, we disclose it in a way viewers can actually see

If you need a release add-on for synthetic use, keep it narrow and explicit.

The participant gives consent for their voice and likeness to be used to create AI-assisted or AI-generated video and audio that may include synthetic performance and a generated setting. This consent applies only to the specific project, versions, and channels agreed in writing. No additional reuse, retraining, or creation of new performances using the participant’s voice or likeness is permitted without further written consent.

Key takeaways

The work that lasts returns to fundamentals, real craft, real choices, real connection.

Use AI for speed and variation, not for borrowed belief

Treat consent and disclosure as part of the craft, not admin

Keep a clear record of your process so authorship is easier to demonstrate

Commissioning brands should demand sourcing clarity and visible disclosure

Hybrid workflows keep the human hand steering, and the output stronger

Used well, AI can widen access to good production and help great ideas travel further. Used carelessly, it can drain trust and make original choices harder to spot. That’s why the human hand steering still matters.