Will AI Replace Human Video Editors by 2030?

Updated January 2026

Editing is the point where a project either becomes deliberate or falls apart. Great footage can be ruined by weak judgement, and rough footage can be rescued by it. That’s why AI in the edit is not just a workflow story, it’s a responsibility story.

It’s also one of the stranger gaps in how the industry hands out respect. Editors rarely get the glory on an Oscars stage, yet they do a huge amount of the heavy lifting that makes a film feel inevitable, and makes a brand video feel credible. And it’s never just “the footage”. It’s music, sound effects, silence, pacing, the tempo of shots, and the small sensory choices that tell an audience what to feel before they’ve consciously decided.

That’s why the current wave of AI in post-production lands differently for editors than it does for everyone else. Runway Gen-4.5 pushed text-to-video into “hang on, that’s believable” territory, and the Adobe + Runway partnership is a signal that this tech is moving closer to everyday creative workflows, not staying in the experimental corner.

But the real shift isn’t just speed. It’s what speed does to the job. When software can generate options in bulk, the bottleneck moves from “how fast can you build a cut?” to “how do you choose what deserves to exist?” That’s a quieter pressure, but it’s the one that’s going to define the next few years.

What’s happening with AI in video editing right now (in 2026)

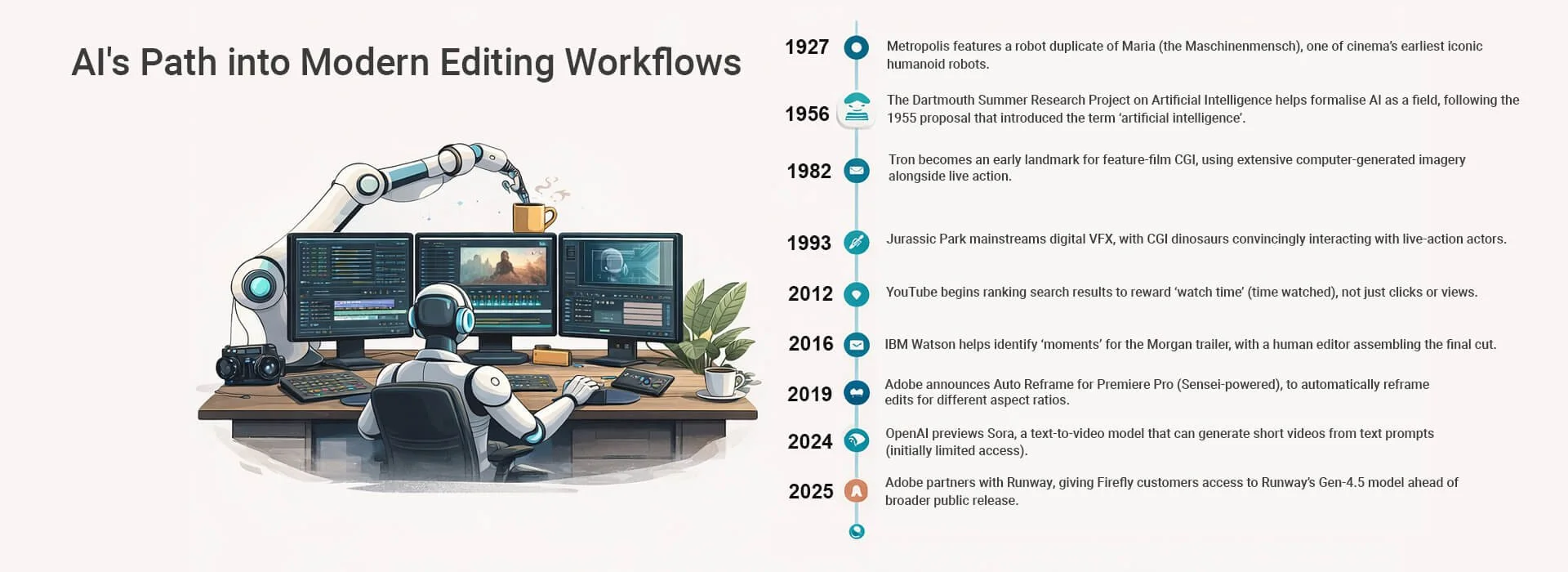

Key milestones in how AI moved from theory and VFX to everyday video workflows, setting up the editorial trust questions editors are now facing in 2026.

Think about the time sinks that don’t add much creative value: first-pass subtitles, cutting dead air, levelling audio, reframing for vertical, removing small distractions, building a rough assembly just to see if the structure works. AI is increasingly taking the first swing at those tasks, which means editors get pulled less into mechanical clean-up and more into shaping what the piece is actually saying.

The interesting bit isn’t that tools are getting faster, it’s where they’re aiming. Adobe’s Runway partnership is about bringing top-end generative video models into mainstream workflows. Descript keeps pushing “edit by text” so the transcript becomes the interface. DaVinci Resolve Studio’s AI IntelliScript goes one step further and can build timelines from a written script, which changes how quickly you can move from intent to a usable cut. Blackmagic Design: What’s New (DaVinci Resolve)

And if you want a grounded look at what these tools do well, and where they still misread human judgement, AI video editing tools is the most natural next step.

When software can generate options faster than any team can review them, editing stops being a technical task and becomes a judgement problem, which is why what we trust when video can be generated sits behind what happens to editors by 2030.

Where AI helps, and where it quietly harms

AI is brilliant at boosting speed and suggesting options from huge libraries of reference patterns. But the work that makes an edit feel alive still sits in human judgement: when to hold back, when to cut early, when to let a silence do the work, when an “improvement” quietly changes the meaning. Those aren’t just technical moves, they’re choices about intention and trust.

This is also where people underestimate the craft. Editing isn’t only selecting pictures. It’s building rhythm, managing energy, placing music and effects so they support the story without announcing themselves, and shaping the viewer’s perception moment by moment. If you’ve ever noticed how a brand film can feel “expensive” before you’ve clocked why, a lot of that is sensory design, not camera specs. If you want a deeper take on that side of the craft, the synaesthetic angle in Synesthesia and brand videos fits surprisingly well here.

This is why it’s cleaner to talk about tasks rather than jobs. A lot of editing involves repeatable activities that can be accelerated or partially automated. McKinsey, for example, argues that activities accounting for up to around 30% of hours worked could be automated by 2030 in the US economy, while also emphasising that many roles will shift rather than simply disappear.

If you zoom out, organisations that aren’t trying to make editing the headline are describing the same pattern: wide impact, uneven disruption, and lots of reshaping. The IMF’s Kristalina Georgieva, for instance, has said AI is likely to affect almost 40% of jobs globally, with outcomes ranging from productivity gains to displacement depending on how it’s managed.

The creative risk worth naming is sameness. If everyone leans on the same model defaults for pacing, colour, transitions, and “good enough” story arcs, you can end up with work that’s frictionless but forgettable. The antidote isn’t rejecting tools. It’s using them to clear the boring fog, then spending your human attention where it counts: meaning, tone, and the responsibility of what your edit implies.

So, will AI replace human video editors by 2030?

Not in the way the question usually means. If “replace” means “the role disappears”, that’s unlikely. If it means “the role changes enough that some editors who only do the technical layer get squeezed”, that’s already happening.

A practical way to think about 2030 is to split editing into two layers. One layer is repeatable production work, the other is interpretive work that creates meaning and carries risk. AI will keep chewing through the first layer quickly. The second layer is the one that becomes more visible, because it’s where trust can be earned or lost.

More automated: assembly from scripts, rough selects, captions, reframes, clean-up, first-pass colour matching, basic sound sweetening, even generating placeholder shots or transitions.

More valuable: story structure, taste, restraint, ethics, meaning, audience psychology, and the ability to defend choices under scrutiny.

The twist is simple: tools that free us for judgement can also drown it in infinite “good enough”, because speed rewards the easiest acceptable choice.

Speed doesn’t kill editors. It just makes taste rarer.

It’s easy to accept a “close enough” option when the tool can generate ten more in seconds. The danger is that convenience starts making the creative decisions for you.

In a real interview edit, the risk isn’t missing a cut point. It’s the temptation to “solve” awkward truth with synthetic smoothness: a generated nod, a cleaner phrase stitched from three takes, a cutaway that didn’t exist. It plays better, sure. It also changes what the viewer thinks they witnessed.

A useful rule of thumb in 2026 is simple: if an AI-assisted change would alter what a reasonable viewer assumes happened, slow down, get explicit sign-off, and make that decision traceable.

Intention isn’t a feature. It’s a responsibility.

An editor who can only operate the software is at risk. An editor who can turn messy reality into a coherent cut is harder to replace, because they can make decisions that hold up under scrutiny, and explain why those choices were right for this story, this audience, this moment..

Where humans still win, even with better models

AI can suggest, imitate, and produce plausible options at scale. What it still can’t reliably do is carry responsibility for what the edit means once it leaves your timeline. Clients rarely ask for “more AI”, they ask for a cut that won’t get questioned, misread, or quietly undermine trust. That’s the gap. The moment context matters, a human editor is doing more than selecting takes, they’re anticipating how a line will land, how a reaction shot will be interpreted, and what a reasonable viewer will assume from the sequence you’ve built.

A few examples that show up in real-world work:

Story truth versus technical polish. Sometimes the cleanest version is the least honest version. Knowing when not to “fix” something is a human call.

Cultural and social context. A model can mimic tone, but it can’t reliably understand what will land as insensitive, misleading, or simply off-key for a specific audience in a specific moment.

Narrative accountability. If your edit makes an implied claim, you may need to justify it later. Human editors understand that the cut creates meaning, not just rhythm.

Taste under constraint. When you’re balancing brand, legal, stakeholder politics, timing, and platform norms, the “best” cut is rarely the most technically impressive one.

This is where editing starts to look less like operating machinery and more like authorship. And authorship is exactly what the “human vs synthetic” conversation keeps circling back to.

Tough ethical questions and what’s next

Using existing footage to train models raises tricky questions about intellectual property and style ownership. Deepfakes raise a different problem: they weaken the basic social assumption that video is evidence of something that happened. That’s why transparency rules are tightening.

In the EU, the AI Act includes transparency obligations for certain AI-generated or manipulated content, including deepfakes. If synthetic media is going to be normal, labelling and disclosure become part of the trust contract.

China is also pushing in the same direction. Regulators announced labelling requirements for AI-generated content that take effect 1 September 2025, aimed at making synthetic material easier to spot and trace.

For editors, this matters because it turns everyday workflow decisions into trust decisions. If you generate a shot to bridge a gap, reconstruct audio to smooth a sentence, or “improve” a face because the lighting was unkind, you’re not just polishing, you’re shaping what the viewer believes happened. The test isn’t whether the tool can do it, it’s whether the finished piece creates an impression you’d defend if someone challenged it later. In 2026, that’s increasingly the difference between an edit that feels modern and an edit that feels quietly suspect.

What matters most from here

AI is going to keep eating the repetitive parts of editing, and that’s not automatically bad. It can free time, lower costs, and make production more accessible. But it also changes what your work is for.

Sure, AI can help. It can clear the grunt work, make experimentation cheaper, and let small teams try ideas that used to be out of reach. The risk is that a lot of content will start to look like it came from the same handful of prompts, with the same rhythm, the same polish, the same safe choices. That’s exactly why human nuance becomes more valuable, not less. The projects that stand out will be the ones where someone makes specific, slightly braver decisions about tone, pacing, silence, and meaning, and can explain why those choices were right for this story, this audience, this moment.

If you want to future-proof yourself as an editor, the target isn’t becoming “the fastest button presser”. It’s becoming the person who can shape meaning, protect trust, and make choices you’d stand behind even if the raw materials, the tools, and the audience expectations keep shifting.

By 2030, plenty of editing will be automated. The question is whether the human layer becomes thinner, or whether it becomes more visible, more valued, and more accountable. My bet is still on the second, but only if we protect the moments that force real choices, and make authorship visible again.