Will AI Kill the Filmmaking Star?

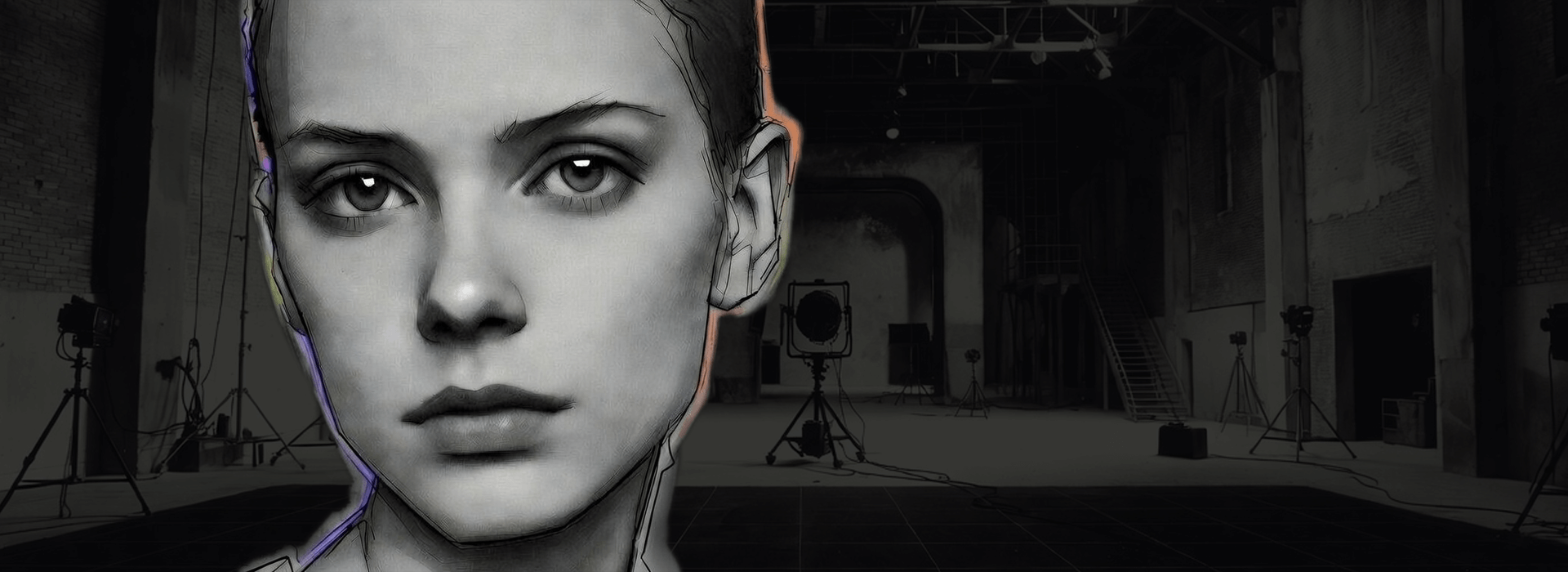

Imagine a clip hits fifty million views in twelve hours and nobody can look away. Everyone’s asking who the girl is. She’s on every screen, framed like a star, quoted like a person, and the internet starts building a biography in real time.

Then it turns out there is no girl. It’s a composite. A still, a prompt, a workflow, a voice. Not a scam exactly, not even hidden, just something that was never meant to be “real” in the old sense. Perfect face. Zero fingerprints.

Scroll again and the question shifts. It stops being about the tool. It becomes about what’s left when “real” gets optional, and when a convincing image no longer implies a living source behind it.

In 1979, The Buggles sang “Video killed the radio star,” a playful warning about technology eclipsing craft. This time the worry feels quieter, and it sits closer to the bone. Not because cameras disappeared, but because authorship is starting to wobble.

New tools are on the horizon that change what a shot even is. A still image can now be turned into motion, and that capability is starting to ship in consumer devices through image-to-video generation inside a gallery app.

When that kind of motion can be produced from almost nothing, “video” stops automatically meaning “a record of something that happened”. Higgsfield says it generates roughly four million videos a day, using OpenAI models for planning and for the video generation step.

Watching systems produce video at that scale, it’s easy to imagine a flood of clips that look cinematic but carry very little weight. Not because they are synthetic, but because nothing had to happen to get them. Once “cinematic” becomes abundant, the question shifts from craft to meaning. What is this for, and what is it asking the viewer to believe.

That doesn’t make filmmaking obsolete. It does make “cinematic” cheaper, faster, and easier to mistake for meaning. The danger is not synthetic images. It’s synthetic certainty, the feeling that a clip is proof when it is really just a product. Perfection spreads, and meaning gets harder to find.

Tech will evolve around us, as it always has. The difference now is that commissioners, platforms, and audiences are all watching what that evolution does to truth, authorship, and consequence. When the supply of polished images explodes, the value of a shot shifts. It stops being about whether it looks cinematic and becomes about whether it feels earned, and whether there is a reason behind it.

Think of Claude Monet’s water lilies. The originals still feel alive because they carry time, attention, limitation, and taste. If a system can generate endless water lily variations on demand, the look survives but the scarcity disappears. The risk for filmmaking is not that style dies. It is that style gets flattened into a cheap default.

That flattening tends to land hardest where speed already wins. Short-form feeds, fast turnaround ads, low-stakes streaming filler. Some of it will look great and feel empty, because it never had to pass through the friction where meaning usually forms.

Left, the wonder of an aurora, expressed in paint. Right, a tulip field, painted with restraint and warmth. Both make the same point. Craft still matters, especially when images are easy to generate.

The Enduring Power of Human Stories

The upside is that audiences often notice what is missing once the novelty wears off. When you watch a run of immaculate clips, the sameness becomes the tell. The image is fine, yet nothing catches.

Human work still has an advantage here, not because it is purer, but because it comes with context and consequence. Documentary does not just record faces. It records consent, risk, and the fact that somebody was there when it mattered. Event films live or die on timing, proximity, and instinct.

Drama depends on choices made under real constraints, including weather, budgets, personalities, and the quiet chaos of a day that will not behave. That chaos is not just inconvenience. It’s often the pressure that produces the thing people actually remember.

Actors are part of that mess in the best way. A pause that lands by accident. A line that changes because someone is tired, annoyed, or trying not to laugh. Those moments are not mystical. They are human signals that something happened in the room.

Some of the moments that make a film were not planned. A glance that changes the temperature of a scene. A prop that breaks and forces a better choice. A line that lands differently because the room is holding its breath. You can rehearse a lot, but you cannot fully design the accidents that give a story its pulse.

These tools will keep improving at the surface. The deeper question is whether they can earn the same kind of trust once viewers start asking where this came from, and who is accountable for it. The real argument shifts fast when a performer is built, not born, and the fight becomes rights, control, and responsibility.

The Bigger Threat: Trust in a Deepfake World

When the clip is shareable, the hard part becomes proving what it is.

The bigger risk is not taste. It is trust.

When synthetic footage is convincing at a glance, video starts behaving like a rumour. You do not only worry about fake films. You worry about fake evidence, fake apologies, and the slow creep where any clip can be dismissed as “probably synthetic” the moment it becomes inconvenient. You watch a clip and you can feel the argument start before the facts arrive. Not “is this true?” but “who benefits if it is?”.

Trust isn’t dying. It’s getting expensive. The awkward part is that a clean, flawless clip can be easier to accept because it asks less of you. No background, no context, no awkward questions about how it was made. But if the work asks nothing of the maker, it can end up asking nothing of the viewer either.

Not in a dramatic way. In a practical way. People want an explanation of what they’re looking at, and they want someone who can stand behind it when the context gets contested. The EU Artificial Intelligence Act’s definition of “deep fake” is explicit about AI-generated or manipulated image, audio, or

It also sets transparency expectations around certain uses, with carve-outs for evidently creative or fictional work, handled in a way that does not ruin the viewing experience. That is not the law telling filmmakers how to make art. It is the law recognising that synthetic media can travel outside its original frame and be treated as reality.

Here is what that looks like in a situation that feels mundane right up until it doesn’t. A late change lands, the reshoot is unlikely, and a synthetic pickup becomes the neat solution. Weeks later, the campaign is challenged and the conversation changes overnight. It is no longer about whether the shot looks good. It is about permission, sign-off, and whether anyone can show what was generated, what was captured, and what was changed.

Or take a documentary. A scene goes out and the first response is not disagreement, it is dismissal. “Probably synthetic.” By the time releases, rushes, and timelines are gathered, the damage has already travelled.

Tools that track an origin trail, meaning a simple record of what was captured, what was generated, and what changed, can help, but they’re fragile in day-to-day distribution. OpenAI’s note on C2PA metadata is blunt about the weak points. It can be removed accidentally or intentionally, platforms often strip metadata from uploads, and a screenshot can remove it too. Where it works, the C2PA standard underpins Content Credentials and a basic record of how media was made, but trust still tends to rest on boring things. Clear permissions. A simple origin trail. A record of process. The ability to show what was done and why, without turning it into a performance. If trust is getting expensive, the cheapest thing you can do is keep your own receipts.

Underneath all of this is the difference between human and synthetic trust signals, and what authorship looks like when almost anyone can generate convincing footage.

The Human Touch Takes Centre Stage

The human touch is not fading. It is becoming easier to spot, because it is attached to things synthetic work still struggles to carry convincingly. Responsibility. Context. Consequence. The fact that someone can stand behind what was made.

In the Academy’s April 2025 rules update, judging is framed around the degree to which a human was at the heart of the creative authorship, even as digital tools evolve.

That is not a verdict on tools. It is a reminder that intention and accountability still matter, especially once audiences start asking where something came from.

If work leans on credibility, a few habits help.

Capture and keep a small origin trail, including a short behind-the-scenes clip, a couple of phone photos, and a timestamped export of key project files.

Get explicit permission when likeness, voice, or scanning is involved, and write down what the permission covers.

If synthetic elements are used, consider a simple disclosure in the credits so it does not become a gotcha later.

Assume stripping happens, so keep originals and exports organised for when a client, commissioner, or viewer asks for context.

None of this guarantees trust. People can still lie, and files can still be moved around. But it gives honest makers something firmer than vibes.

Being a celebrity used to mean something. It implied there was a person behind the image, a trail of choices, and a public cost when they got it wrong. If a “star” can be assembled, performed, and distributed without a body in the room, then the word starts to loosen.

So when a “star” can be prompted from a photo, what survives?

The infinite copy, or the one you can still feel was earned?